Image source: Getty Images

With a share price of less than £1 and a market cap below £100m, Helium One Global (LSE:HE1) meets the definition of a penny stock. These types of shares — and the Tanzanian gas explorer is a good example — can be high risk. A low stock market valuation is often a sign of a company in its infancy. Typically, they’re loss-making and/or pre-revenue.

But Helium One has discovered gas and is now in the process of applying for a mining licence.

It’s successfully flowed helium at a concentration of 5.5%. For comparison, the world’s biggest discovery was 13.8%. But anything over 0.3% is considered to be commercially viable.

Helium is the earth’s coldest element, which makes it ideal for medical applications. NASA’s believed to be the world’s biggest single buyer as it’s essential for space exploration.

And despite being the second-most abundant gas in the universe, helium is scarce on earth. This makes it one hundred times more valuable than natural gas.

The next steps

If Helium One’s able to successfully establish production in Tanzania, I’m confident that the company will be commercially viable. There’s strong demand for helium and a finite supply. Therefore, at first sight, the prospect of buying the penny share appeals to me.

Just imagine, if an investor put £20,000 (the annual allowance of a Stocks and Shares ISA) into the stock today and the share price rose to (say) 50p — they’d be a millionaire!

For this to happen, the company’s market cap would have to increase to £2.8bn. This would bring it close to becoming a member of the FTSE 100. There are plenty of other large mining companies around so this could happen.

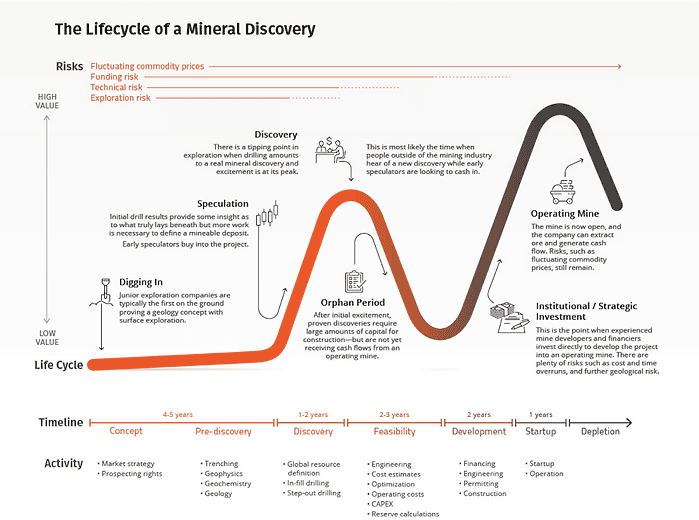

And a look at the company’s stock market valuation suggests it could be following the path predicted by the Lassonde Curve (see below), which charts the typical life cycle of a mining stock.

After an initial period of hype, followed by a discovery of metal or gas, a miner’s valuation generally hits a low point, known as the ‘orphan period’. I think this is where Helium One is currently.

But once a path to commercialisation is established, the Lassonde Curve predicts that its market cap should then start to pick up.

However, there are many obstacles that need to be overcome before this becomes a realistic prospect. The biggest of which is the need to raise lots of money. And this means dilution for existing shareholders, unless they participate in any fund raising.

On listing, the company had 139m shares in issue. It now has 5.9bn in circulation. It recently had to issue 15.7m to pay a key supplier. In my opinion, this is a bit like offering an energy supplier a share of your house in return for waiving an electricity bill.

What does this mean?

Going back to my example of a £20,000 investment, let’s say the company has to raise £250m (approximately five times its current market cap) to start generating revenue.

The investor’s ownership of the company would then be diluted by over 80%. This wouldn’t be a problem if the value of the company increased by a similar amount. But that’s unlikely because each round of fund raising is likely to take place at a discount to the prevailing share price.

That’s why I don’t want to invest in Helium One.

Credit: Source link