A boom in infrastructure projects linking Hong Kong to the surrounding Pearl River estuary is blurring the already hazy border separating the former British colony from mainland China.

Beijing, which took possession of Hong Kong in 1997, sees the city — and particularly its global financial services industry — as a linchpin of the Greater Bay Area, an 11-city megalopolis comprising China’s manufacturing heartland including nearby Shenzhen, Macau and Zhuhai. This region’s collective gross domestic product was Rmb12.6tn ($1.97tn) in 2021, surpassing South Korea’s.

Projects such as the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, a 55km system of tunnels and the world’s longest sea bridge, which opened in 2018, is just one piece of an increasingly complicated jigsaw of infrastructure linking Greater Bay Area cities. Others include rail lines, bridges, special economic zones and massive real estate projects that open up vast economic opportunities for Hong Kong.

Critics, however, say the projects are doing with infrastructure what Beijing is simultaneously doing with legislation — gradually eroding Hong Kong’s autonomy. “It is clear that they really want to dissolve the border,” said Ho-fung Hung, a professor at Johns Hopkins University and author of City on the Edge: Hong Kong under Chinese Rule.

The city was returned to China in 1997 after 156 years of British rule, and was meant to be self-governed. But gradually Beijing has ended any semblance of the “one country, two systems” formula that had been agreed at the time of the handover. That culminated in a security law promulgated in mid-2020 that all but erased the special administrative region’s sovereignty.

Hung said economic and social integration between Hong Kong and the mainland began as early as 2003, when the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement was signed by Hong Kong and Beijing.

Official plans to economically integrate the southern cities came in 2017, when Hong Kong signed a framework agreement to deepen co-operation with Macau and Guangdong province.

The following year, Chinese President Xi Jinping called for further integration. “The integration of Hong Kong and Macau into the overall development of the country is the proper meaning of ‘one country, two systems’,” he said.

Further integration was halted by the pandemic, as China’s harsh zero-Covid curbs closed the border with Hong Kong.

However, as China resumes quarantine-free travel, a new wave of cross-border traffic will quickly take shape as recently completed infrastructure projects unify the two jurisdictions.

“Economic integration is to be accelerated, especially when Covid is now fading away and the border gate between Hong Kong and China is going to open,” said Sonny Lo, veteran political scientist and observer of the politics of Hong Kong and Macau.

“In the long run, approaching 2047, we can’t expect the territorial boundary for Hong Kong to remain unchanged,” said Lo, referring to the end of the 50-year agreement for the “one country, two systems” formula.

Hong Kong’s economic and political integration with the mainland continues apace. Bit by bit, Hong Kong’s sovereignty is being chipped away.

After Beijing imposed the 2020 security law on Hong Kong, the state security agency established an office temporarily taking over the Metropark Hotel Causeway Bay in July 2020.

The office, founded by the Chinese government, is not subject to Hong Kong jurisdiction. Since then, more than 200 people have been arrested by national security officers for acts that the authorities deem as secession, subversion, collusion with foreign forces and terrorism, which can lead to life imprisonment.

It represents the latest addition to the steadily increasing presence by China’s security services. The Hong Kong garrison of the People’s Liberation Army is headquartered in Central and owns 19 military sites, which span a total of roughly 27 sq km, according to the government.

In 2022, ahead of the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover to China, Major General Peng Jingtang vowed to be combat-ready for any “tough and complicated” contingencies.

But political sticks are accompanied by economic carrots: policies such as one recently announced by Guangdong province that will allow Hong Kong residents living in Hong Kong to commute and work in the Greater Bay Area. Paired with increasing infrastructure projects that will boost cross-border flows, Hong Kong’s economic uniqueness could soon fade away.

This article is from Nikkei Asia, a global publication with a uniquely Asian perspective on politics, the economy, business and international affairs. Our own correspondents and outside commentators from around the world share their views on Asia, while our Asia300 section provides in-depth coverage of 300 of the biggest and fastest-growing listed companies from 11 economies outside Japan.

Subscribe | Group subscriptions

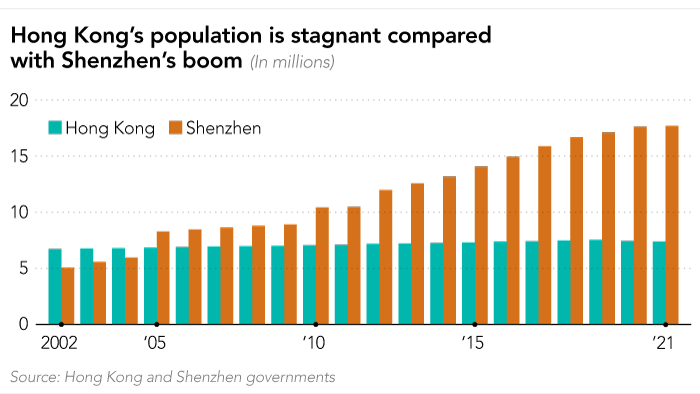

“China has always had a complete, geoeconomic, geopolitical, territorial integration strategy,” political scientist Lo said. “Physical and territorial integration is inevitable. The question now is a migration and population problem: how can you facilitate movement further up north?”

Editors: Charles Clover, Alice French Design: Michael Tsang, Alice French Graphics: MinJung Kim, Hidechika Nishijima, Naomi Hakusui, Michael Tsang Copy editor: John Geis

A version of this article was first published by Nikkei Asia on January 18 2023. ©2023 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved

Related stories

Credit: Source link