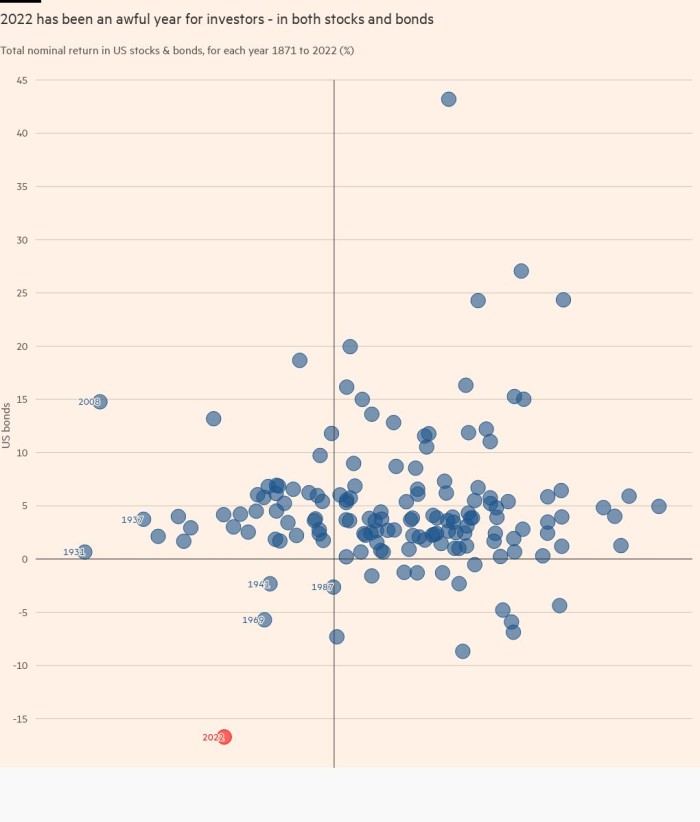

For most investors, 2022 has been a year to forget. Crumbling equities were bad enough, but with bonds also suffering from a surge in inflation and an aggressive response from central banks, fund managers were often left with nowhere to hide. Flinty hedge funds able to bet on the dollar and against government debt are among the few celebrating a good year.

It has also been a year pockmarked by truly extraordinary events, in areas as staid as UK government bonds and as wild as crypto. Here, Financial Times reporters have picked their markets charts of the year, encapsulating the biggest moments and most powerful trends.

The bond market that turned

Soaring inflation and a global dash higher in interest rates have spelt a miserable year for bond investors.

The 16 per cent drop in the Bloomberg global aggregate bond index — a broad gauge of sovereign and corporate debt — is the worst performance in data stretching back to 1991, dwarfing all the other relatively rare annual downturns for fixed income over the past three decades.

At the start of 2022, investors and central bankers were still clinging to the idea that runaway inflation could be tamed through relatively modest rises in interest rates. But the commodity price shock resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine put paid to those hopes. Inflation continued to surprise on the upside for most of the year, even as central banks in the US, UK and eurozone embarked on one of the most rapid tightening cycles in history.

The US 10-year Treasury yield — a benchmark for global fixed income — peaked at above 4.3 per cent in October, having started the year at around 1.5 per cent, helping to fuel a 20 per cent drop in global stocks. Yields have since fallen back to 3.9 per cent following signs that US inflation is slowing — the latest data covering November show a pullback to a relatively tame 7.1 per cent in the annual rate, down from a peak above 9 per cent earlier in the year. But investors will be looking for further confirmation that price pressures are easing in the US and elsewhere before calling the end of a brutal bond sell-off. Tommy Stubbington

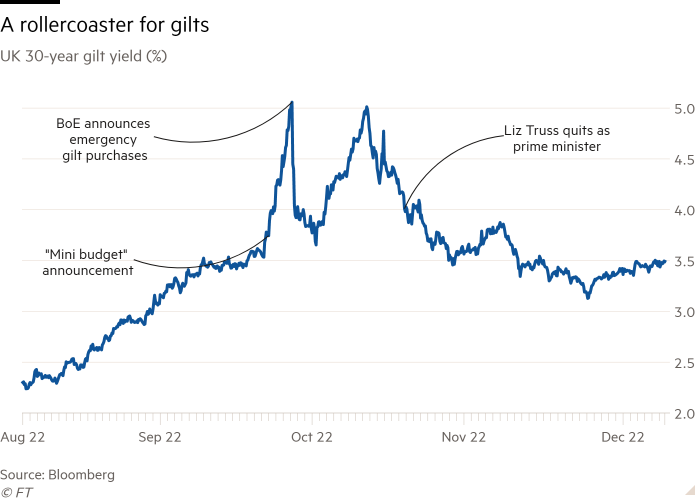

Gilts gone wild

Even in a year of unprecedented bond market volatility, the UK stood out. When Liz Truss, in her 44-day spell as prime minister, came up with a £45bn package of unfunded tax cuts in September, the gilt market crumbled.

Investors were unnerved not just by the scale of the planned borrowing, which came on top of the sizeable bill for a widely anticipated household energy subsidy, but also the decision to push ahead without analysis from the official budget watchdog.

The price of gilts cratered, sending yields rocketing higher. This in turn sparked a crisis in the UK pensions sector, where many so-called liability-driven funds had loaded up on leveraged bets on low yields and urgently needed to meet margin calls. As they dumped long-dated gilts to raise the necessary cash, the market for UK government debt entered a “self-reinforcing” downward spiral, according to the Bank of England, which was forced to step in with an emergency bond-buying programme. The swings in 30-year gilt yields on September 28, when the BoE first stepped in, were larger in that single day than seen in most years.

Calm truly returned to the gilt market only with the resignation of Truss and the ditching of her tax cuts by successor Rishi Sunak. It was widely seen as a victory for the so-called bond vigilantes in chastening a government that had overstepped the bounds of responsible fiscal policy. Tommy Stubbington

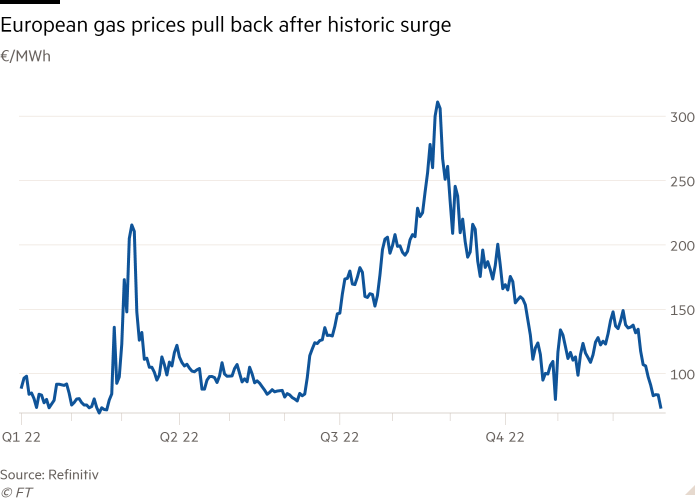

NatGas: flame thrower

If there’s one commodity that tells the tale of 2022 it is natural gas, where Europe learned a rough lesson in energy geopolitics.

Having been reliant on Russia for 40 per cent of its gas prior to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU’s scramble to replace supplies from Moscow has dominated all other markets.

The Russian squeeze on gas supplies started before the invasion as Moscow sought to soften up Europe for what was to come. But it reached its pinnacle this summer when exports on the key Nordstream 1 pipeline to Germany were cut.

By August, prices had risen above €300 per megawatt hour — or more than $500 a barrel in oil terms — stoking a cost of living crisis, runaway inflation and even fears of economic meltdown.

But the market worked. Europe got enough gas into storage to start the winter, sucking in endless cargoes of liquefied natural gas while curtailing demand. So far there have been no outright shortages. Prices remain eye- wateringly high compared with the norm, but they have more than halved since August.

Now, concerns are already shifting to next winter, with a big question over whether Europe can refill storage again while Russian supplies are almost completely cut off. David Sheppard

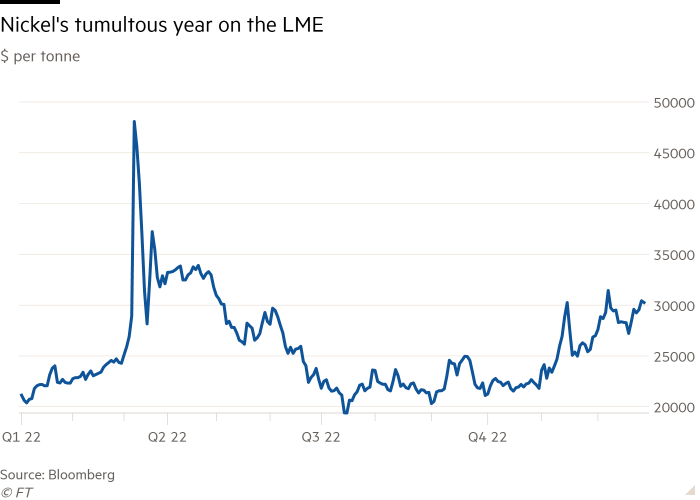

The LME’s great nickel pickle

Nickel is usually a humdrum commodity used in stainless steel with a sexy growth story for its use in electric vehicle batteries, but it hit the headlines for all the wrong reasons in March.

The metal had been trading at an average of $15,000 per tonne for years. But prices surged 280 per cent to more than $100,000 per tonne in a single day, as fears of sanctions on Russia — a large nickel producer — rubbed up against a bet on falling prices by Tsingshan, the world’s largest stainless steel company that has been building out vast nickel projects in Indonesia.

The historic price increase led the London Metal Exchange to suspend and cancel billions of dollars’ worth of trade, sparking one of the biggest crises in the 145-year-old bourse’s history as participants that stood to profit claimed damages of almost $500mn and traders questioned why nothing was done sooner.

The full extent of the crisis was later revealed in the LME’s defence against legal claims. Cash requirements for trading would have pushed clearing members into bankruptcy, which would have spiralled the LME’s clearing house into default and even risked contagion across the financial markets.

Since the trauma, traders have pulled away from using the LME contract for nickel, which serves as the global benchmark for producers and sellers to strike deals. The thin liquidity has led to a return to volatile swings in prices.

The nickel market mess is far from over — the LME will find no quick fixes for restoring faith in its contract and tarnished reputation. Harry Dempsey

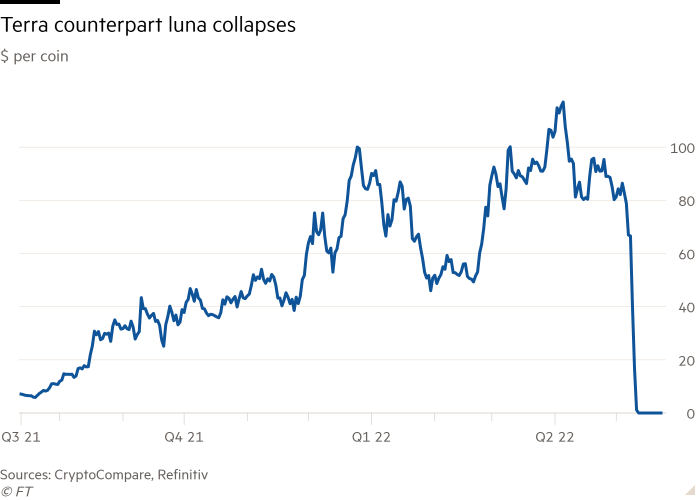

When crypto cracked

The cryptocurrency industry is suffering its own “Lehman moment” of sliding asset prices and a daisy chain of failures in overleveraged and often poorly managed market intermediaries. The biggest of them all, of course, is defunct FTX, whose founder Sam Bankman-Fried is now feeling the full force of criminal and civil cases that could land him with a century-long prison term. The foundations for this crisis were laid at crypto’s inception, but the spark for the meltdown came in May.

That was when the terra crypto token — brainchild of now on-the-run Terraform Labs founder Do Kwon — imploded. The so-called “stablecoin” was supposed to hold a solid $1-a-piece valuation under a scheme backed by algorithms and blind faith. But in May, its value collapsed to zero and pulled large chunks of the crypto space down with it, starting with its sister token luna.

An abridged history of what happened next includes the failure of crypto hedge fund Three Arrows Capital, which fell in to liquidation in June; Celsius Network (tag line: “debank yourself”), which filed for bankruptcy in July; and a host of other intermediaries that were, ironically, bailed out at the time by Bankman-Fried. Scott Chipolina

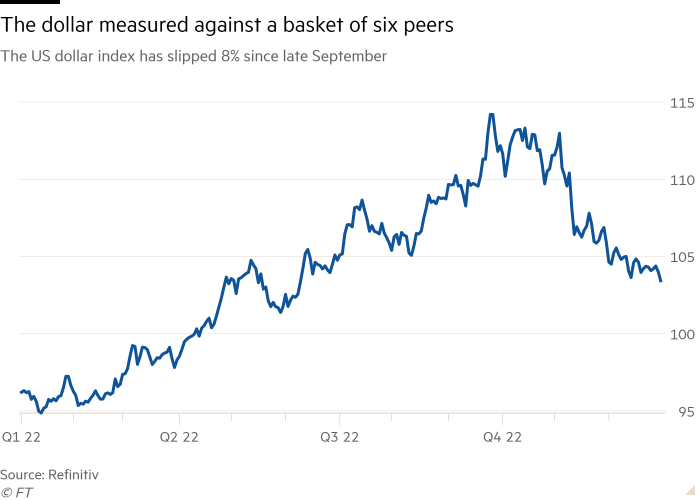

The year of King Dollar

In a messy year for markets, one constant has been the US dollar, which cranked up to a 20-year high in September compared with a basket of six other major currencies — an ascent of 26 per cent from May 2021.

The buck has laid waste to a host of other currencies, including the euro, which sank to parity against the dollar in July, and sterling, which cratered to an all-time low after September’s disastrous “mini” Budget. China’s renminbi also hit its lowest point since 2007, while Japan has broken with tradition and intervened heavily to strengthen the yen — which it has spent years trying to push down, not up.

Support for the dollar has come from investors’ search for a haven to park their cash as rising inflation and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have hammered global financial markets.

Now, US inflation appears to be turning lower and the dollar is, too. Slowing US economic growth and growing expectations of a so-called Federal Reserve “pivot” to slower rate rises, or even cuts, in 2023 amount to a “recipe for a weaker dollar”, says Kit Juckes, a macro strategist at Société Générale.

Others are not so sure. The greenback may have peaked, they argue, but that does not mean it is set to continue tumbling next year.

“Our baseline view is that central banks’ tightening into recessions will keep the dollar supported a little longer than most expect,” says Chris Turner, global head of markets at ING. George Steer

How the rouble got out of trouble

Russia’s rouble became an unlikely comeback kid this year. It is stronger against the dollar today than it was before Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, having rebounded following a sharp decline in the first weeks of March.

The currency initially tumbled in value following the outbreak of war, falling to around 130 against the dollar in the days and weeks after Russia’s central bank more than doubled interest rates to 20 per cent in late February to calm the country’s financial markets.

Its resurgence does not reflect a wave of investment back in to Russia, however. Instead, Putin’s imposition of tight capital controls and blocks on foreign traders looking to exit their investments helped the rouble recover those losses by April.

The end of the year brought a renewed spell of rouble weakness, leaving the currency at 72 to the dollar. George Steer

Credit: Source link