The deflating bubble in digital assets has exposed a fragile system of credit and leverage in crypto akin to the credit crisis that enveloped the traditional finance sector in 2008.

Since its inception, crypto enthusiasts have promised a future of vast personal fortunes and the foundations for a new and better financial system, dismissing critics who questioned its value and utility as spreading “FUD” — fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

But those emotions are now stalking the crypto industry as one by one, often-interlinked projects that locked up customers’ money face losses of millions of dollars and turn to the industry’s heavy hitters for rescue packages.

“Fear is contagious. That’s true in any financial market . . . No one wants to be the last person without a chair when the music stops, so everyone is withdrawing money,” said Brett Harrison, president of crypto exchange FTX US.

The price of bitcoin, the largest cryptocurrency, has fallen more than 70 per cent since its peak in November and the total value of crypto tokens has dropped from above $3tn to less than $900bn.

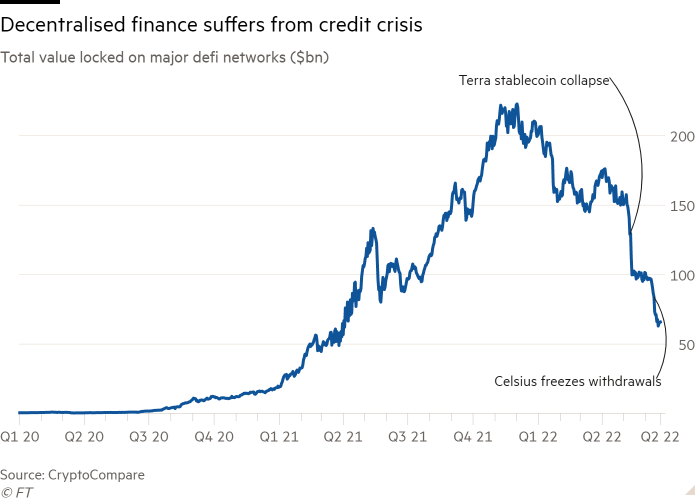

As the market shrinks, the industry is creaking. A token called Luna and its sister Terra, a stablecoin that tried to use computer algorithms to keep its price steady, collapsed in May; crypto lender Celsius halted withdrawals earlier this month; and hedge fund Three Arrows Capital faced margin calls.

In recent days, another lender, Voyager, has limited withdrawals while exchange Coinflex has frozen client funds. Trades and investments that appeared safe, liquid and profitable a few weeks ago have become perilous and impossible to exit. Investors are fearful that more dominoes are about to fall.

At the heart of the boom has been the growth of decentralised finance, known as DeFi, a corner of the crypto world that claims to offer an alternative financial system without central decision-making authorities like banks or exchanges. Instead, users can transfer, lend and borrow assets by using contracts that are defined in computer code. Changes are not made by chief executives but votes from those who own special governance tokens, often developer teams and early investors.

The amount of capital circulating in DeFi projects had soared to nearly $230bn by late 2021, according to CryptoCompare data.

In the last crypto boom, in 2017, buyers simply speculated on token prices. This time, small investors and some funds have also sought out high yields from lending and borrowing crypto assets.

That appealed to both sophisticated crypto traders and to public-facing lending platforms like Celsius, which took in customer deposits and paid out interest rates as high as 17 per cent.

Investors could juice their returns by taking out multiple loans against the same collateral, a process called “recursive borrowing”. This freedom to recycle capital with little restraint led investors to stack up more and more yields in different DeFi projects, earning multiple interest rates at once.

“As with the subprime crisis, it’s something really appealing in terms of yield and it looks like and is packaged like a risk-free financial product to ordinary people,” said Lennix Lai, director of financial markets at crypto exchange OKX.

The financial gymnastics left huge towers of borrowing and theoretical value teetering on top of the same underlying assets. This kept going while crypto prices sailed higher. But then inflation, aggressive interest rate rises and geopolitical shockwaves from the war in Ukraine washed across financial markets.

“It all worked during the bull run where the prices of all the assets went up only. When the prices started going down, a lot of people wanted to take their assets out,” said Marcin Miłosierny, head of market research at crypto hedge fund ARK36.

As token values plummeted, the lenders called in their loans. The process has led to the removal of more than 60 per cent, or $124bn, of the total value locked on the ethereum blockchain since mid-May in a “Great Deleveraging”, according to research firm Glassnode.

The first domino fell in May, when Terra failed, rattling investor confidence. Next came lender Celsius, which froze client accounts when it was caught in a severe liquidity mismatch on its books.

Last week Three Arrows Capital, a major Singapore-based crypto hedge fund, hit the skids after it was unable to meet margin calls. Voyager has confirmed it could be exposed to Three Arrows defaults. BlockFi and Genesis also liquidated at least some of Three Arrows’s positions, according to people familiar with the matter.

The situation has been exacerbated by the heavy use of borrowing by crypto traders to increase the upside of their market bets. In a falling market, traders face calls for more funds to support their positions.

“There is a snowball effect. Whenever the bitcoin goes down in price, more people are obliged to sell bitcoin, exaggerating the selling,” said Yves Choueifaty, chief investment officer of asset management firm Tobam.

But some executives wonder if crypto has already experienced its own “Lehman” moment, with Celsius the biggest name to fall. They hope the mood is shifting towards action to stabilise the market.

Without a central bank in crypto, they are pinning their optimism on intervention from the industry’s leading lights, notably Sam Bankman-Fried, the 30-year-old billionaire founder of exchange FTX.

Over the past nine days through his companies, Bankman-Fried has extended loans worth hundreds of millions of dollars to BlockFi and crypto lender Voyager to steady both companies and boost confidence in the system.

Bankman-Fried’s moves to act as a lender of last resort include an element of self-interest. His Alameda Research trading firm is the largest shareholder of Voyager, with a 11 per cent holding after buying shares last month. It will also become the “preferred borrower” for any future Voyager lending.

In the last week the price of bitcoin has held steady at around $20,000. But many wonder if the respite is temporary.

“The risk of contagion in the crypto markets remains elevated,” said Marion Laboure, senior strategist at Deutsche Bank. “A tightening Fed will expose more crypto firms with excess credit risks by withdrawing liquidity and raising rates, which will depress the value of the coins on which many of these levered schemes depend,” she added.

Bitcoin was invented at the height of the 2008 financial crisis as an alternative to the financial system, frequently lauded by fans as being immune from the impact of inflation and politically tinted monetary policy.

Many executives are now coming to the conclusion that the crypto industry can be subject to the same booms and busts as other markets.

Global central banks held interest rates ultra-low for a decade to boost economic growth, and pushed those policies even harder in the pandemic. Plenty of that cheap central bank money had trickled down into crypto.

Venture capital firms alone have ploughed $38bn in to blockchain start-ups since 2020, according to Dealroom data. Now, the tide is moving out as the Federal Reserve and other central banks shift to tackling intense inflation.

“In a higher-rate environment, the emperor needs to be wearing some clothes to survive,” said Taimur Hyat, chief operating officer of $1.5tn asset manager PGIM.

That may push consumers, with little legal protection or transparency on the economic health of the companies behind crypto projects, to withdraw funds or show greater caution.

“Anyone who is coming into the space in the next couple of years . . . will have a natural aversion to perpetual motion machines and things that sound too good to be true,” said Sidney Powell, chief executive of DeFi protocol Maple.

“When people go through a big markdown in asset values and breaches of trust, I think that’s what immunises people for the next several years, so in that sense it is like crypto’s 2008.”

Credit: Source link