Italy is the eurozone country most susceptible to a debt crisis as the European Central Bank raises interest rates and buys fewer bonds in the coming months, economists say.

Nine out of 10 economists in a Financial Times poll identified Italy as the eurozone country “most at risk of an uncorrelated sell-off in its government bond markets”.

Italy’s rightwing coalition government, which took power in October under prime minister Giorgia Meloni, is attempting to follow a path of fiscal rectitude. It has budgeted for the country’s fiscal deficit to fall from 5.6 per cent of GDP in 2022 to 4.5 per cent in 2023 and 3 per cent the following year.

But Italian public debt remains one of the highest in Europe at just over 145 per cent of gross domestic product. Marco Valli, chief economist at Italian bank UniCredit, said the country’s “higher debt refinancing needs” and “potentially tricky” political situation left it most vulnerable to a sell-off in bond markets.

Rome’s borrowing costs have risen sharply since the ECB started to increase interest rates last summer. The 10-year bond yield climbed above 4.6 per cent last week, almost quadruple the level of a year ago and 2.1 percentage points above the equivalent yield on German bonds.

Meloni has expressed dismay at the ECB’s’ willingness to carry on raising rates despite the risks to growth and financial stability. “It would be useful if the ECB handled its communication well . . . otherwise it risks generating not panic but fluctuations on the market that nullify the efforts that governments are making,” she said at a press conference last week.

The new Italian government had “given investors few reasons to worry for now”, said Veronika Roharova, head of euro area economics at Swiss bank Credit Suisse. “But concerns could resurface as growth slows, interest rates rise further and [debt] issuance picks up again,” she added.

ECB rate-setters have insisted they will continue to raise rates in half-point increments during the early months of this year. Klaas Knot, Dutch central bank governor and one of the governing council’s hawks, told the FT the central bank was only just beginning the “second half” of its rate-increasing cycle.

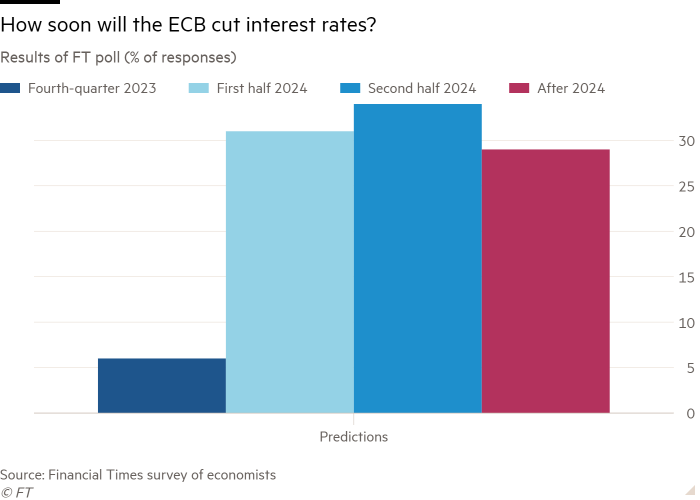

However, analysts believe the ECB is overestimating the risks to inflation — and underestimating the prospect of a recession. IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva said at the weekend that half of the EU will be hit by recession this year. Four-fifths of the 37 economists polled by the FT in December forecast the ECB would stop raising rates in the first six months of 2023 and two-thirds predicted it would start cutting them the following year in response to weaker growth.

On average they predicted that the ECB’s deposit rate would peak at just under 3 per cent, below the level investors are betting on as indicated by the price of interest rate swaps.

A separate FT poll of more than 100 leading UK-based economists said that Britain would endure one of the worst recessions and weakest recoveries in the G7 in 2023.

Central banks around the world have been raising rates sharply to tackle inflation, which has surged to multi-decade highs in many countries, as energy and food prices soared following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the ending of coronavirus pandemic lockdowns pushed up demand for goods and services.

The ECB was slower than many western central banks to start raising rates, but since last summer it has tightened policy at an unprecedented pace, lifting its deposit rate from minus 0.5 per cent to 2 per cent in six months.

“The ECB was too slow [in] recognising that inflation was not temporary, but is now getting up to speed,” said Jesper Rangvid, professor of finance at Copenhagen Business School. “I am still afraid, though, that ECB will not tighten enough because of troubles this would cause in Italy.”

The ECB is due to start shrinking its €5tn bond portfolio by €15bn a month from March by only partially replacing maturing securities, putting further upward pressure on Italian borrowing costs. Ludovic Subran, chief economist at German insurer Allianz, said the eurozone risked a repeat of the bloc’s 2012 bond market meltdown “as fiscal capabilities are different across countries without the ECB’s heavy lifting”.

Italian cabinet ministers have criticised the ECB over its aggressive monetary tightening. Defence minister Guido Crosetto wrote on Twitter that the ECB’s policies “made no sense” while deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini said higher rates “will burn billions in Italian savings”.

Silvia Ardagna, chief European economist at UK bank Barclays, said Italy’s “high stock of debt, elevated fiscal deficit and need of additional energy support measures . . . makes markets very concerned”.

The ECB has unveiled a new bond-buying scheme, known as the transmission protection instrument, which is designed to tackle an unwarranted rise in a country’s borrowing costs. However, more than two-thirds of the economists polled by the FT in December said they expected the ECB to never use it.

Mujtaba Rahman, managing director for Europe for the consultancy Eurasia Group, said a deeper than expected recession next year “could put high-deficit, high-debt countries under even more pressure” adding that this would “probably make for a softer path for monetary policy by the ECB”.

Additional reporting by Amy Kazmin in Rome

Credit: Source link