The UK is in the throes of the kind of labour unrest not seen for decades. This is visible in the railways, London Underground and British Airways. Teachers and other public sector workers may join in. The explanation for this is clear. Unanticipated inflation delivers losses everybody wants to recoup. This triggers social conflict.

Yet if inflation is bad, so is the cure. Unless one believes it will magically disappear, the way to end entrenched inflation is via a period of below trend output and rising unemployment. This will be “stagflation” — a combination of high inflation with weak growth that lasts for some time and might require more than one tightening before it ends.

Start with the inflationary process itself: how far is the inflation imported and how far is it due to excessive domestic demand?

In the UK, the price level for goods other than energy and food has risen by 8 per cent over the past two years. The comparable figure in the US is 10 per cent. In the eurozone, however, it is only 4.7 per cent. This supports the view that the domestic inflationary dynamic in the UK (and US) has been stronger than in much of the eurozone.

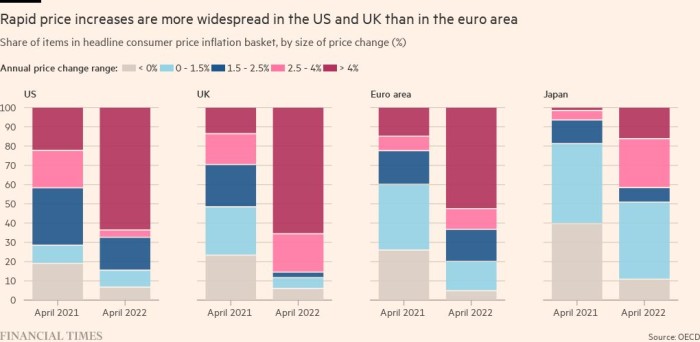

The latest Economic Outlook from the OECD also shows that the inflationary process is now widespread in the UK. Thus, the proportion of goods and services with annual inflation running at over 4 per cent rose from 14 per cent to 66 per cent between April 2021 and April 2022. Finally, the ratio of unemployed workers to the number of vacancies was lower in the first quarter of this year in the UK than in the previous two decades. The US situation is similar.

The OECD also forecasts that UK headline inflation will still be running at 4.7 per cent at the end of next year. Inevitably, then, people will seek to recover the large losses in their standards of living. This means that there will be strong pressure for higher wages. This pressure will be further strengthened by a growing lack of confidence in the Bank of England’s ability or determination to hit its inflation target. Contrary to what some in central banking circles believe, inflation targets are not hit because they are credible: they are credible because they are hit. But if wages do indeed catch up with past (and expected) rises in prices, a further spiral of domestically generated inflation will emerge, partly offsetting any diminution in the rate of imported inflation.

In sum, in countries like the UK and US, the economy must be weakened enough to eliminate the domestic overheating and remove the likelihood of a destructive wage-price spiral.

This raises two questions: how big a weakening will be needed and how is it going to be delivered?

An optimistic view on the first question is that taking just a little bit of excess from the labour market will be enough to remove the risk of a domestic inflationary spiral. This seems highly improbable. Given the reductions in real incomes that have occurred, workers will expect and receive catch-up increases in wages in any reasonably robust labour market. It is likely that unemployment will have to rise substantially if this is to be limited.

The answer to the second question depends on how far such a slowdown is going to happen anyway. The view that it will happen anyway notes the contractionary impact of higher prices of energy and food, fiscal tightening (in part because cash limits will bite in real terms), likely reductions in growth of credit as confidence deteriorates, falling asset prices and the war in Ukraine. Thus, the UK economy will be forced to slow down directly, but also indirectly, because the world economy has slowed. The OECD’s forecast for the UK for next year is for zero growth.

Will even more than this need to happen to bring inflation down to target? Possibly not, particularly if, as seems plausible, actual growth will be even lower than forecast next year. But the longer this inflation continues, the harder it will be to regain the target. It is possible that deliberate policy tightening will need to be greater than now expected.

The market currently expects the Bank of England’s short rate to peak at around 3 per cent a year from now. That would still be a substantially negative in real terms rate under any plausible inflation expectations. This looks a mouse of a rate, given the scale of current and prospective inflation overshoots.

Central banks have made big mistakes, as Mervyn King has argued. At present, the Bank like other central banks hopes that a very modest tightening will do the trick. If it does, it will be because the economy is going to slow a great deal anyway. Bad times lie ahead. The question is how bad.

martin.wolf@ft.com

Follow Martin Wolf with myFT and on Twitter

Credit: Source link