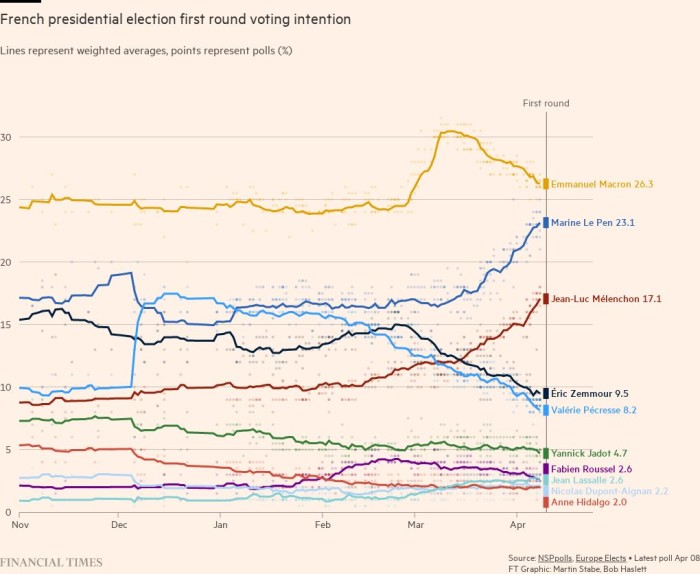

France will vote on April 24 whether to give President Emmanuel Macron a second five-year term or entrust the presidency to his rightwing challenger Marine Le Pen.

The race is a repeat of the 2017 election, in which Macron decisively defeated Le Pen with 66 percent of the vote. The latest polling points to a far narrower outcome in this election.

Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron, the centrist incumbent, won the first round with 28 per cent of the vote. His comfortable early lead in the polls narrowed significantly in the last weeks before the vote, prompting Macron to warn he could lose to the far right.

The tightening polls led supporters to worry he had spent too much time responding to the war in Ukraine, which initially boosted his ratings, instead of campaigning. Macron sought to play a leading role in diplomatic efforts to prevent the war and still holds frequent calls with Vladimir Putin and Volodymyr Zelensky to try to broker peace.

Macron’s campaign focuses on his efforts to liberalise the economy, including plans to increase the retirement age. France’s strong post-pandemic economic recovery boosted his pre-election poll ratings. Now he must convince voters that he is more than a president of the rich and can unite a fragmented France, and that he can be trusted with immigration, a key battleground in the debate.

Marine Le Pen

Far right veteran and leader of the Rassemblement National, Marine Le Pen, came second with 23 per cent of the first-round vote. She re-emerged strongly in the polls after fending off candidates from the extreme right and the far left and could become France’s first female president.

Analysts say her campaign’s pivot away from immigration to the cost of living crisis has helped her widen her voter base. Le Pen’s strong comeback suggests her attempts to “detoxify” her party’s racist image have paid dividends with the public, despite alienating some loyal supporters, including her niece Marion Maréchal, who declared her support for extreme-right rival Eric Zemmour.

Le Pen is sceptical of the EU and Nato and has longstanding ties with Putin, which she has recently tried to downplay. She is campaigning under the slogan “Give the French their country back” and wants to rewrite the constitution to give France new powers to tightly control its borders and cut off immigrants from housing subsidies and healthcare.

The two remaining contenders topped a field of 12 candidates in the first round of voting on April 10:

Jean-Luc Mélenchon

Jean-Luc Mélenchon, a leftwing veteran who founded La France Insoumise, or “France Unbowed”, after defecting from the Socialist party, is the leading candidate on the left of French politics. He wants to lower the retirement age to age 60, legalise cannabis and welcome migrants. With France’s fractured left unable to unite behind one candidate, his chances of reaching the second round look slim, although he has risen slightly in the polls.

Eric Zemmour

Eric Zemmour, an anti-immigration television polemicist recently convicted of hate speech, came from nowhere to reach second place in the polls last autumn by calling for “immigration zero” and criticising Le Pen as incapable of winning. His new party called Reconquest has offered a harder line alternative for conservative and far-right voters. But the war in Ukraine has weakened his position by reminding voters of his support for Putin and pushing his main issues – immigration and crime – down the list of priorities.

Valérie Pécresse

Valérie Pécresse, elected leader of the Île-de-France region around Paris, won the nomination for the centre-right Les Républicains. Polls had initially suggested she could pose a serious challenge to Macron in a run-off but her support has since waned. Self-described as two-thirds Angela Merkel and one-third Margaret Thatcher, Pécresse has taken a hard line on immigration, wants to slash public spending and fight sexual harassment. She must win over centrist voters and conservatives who are flirting with candidates from the far right.

Yannick Jadot

Yannick Jadot, an MEP and leader of the Green party Europe Ecologie-Les Verts, calls himself a pragmatic environmentalist. He led the Greens to third place in the EU elections in 2019 and like Macron he refuses to be branded as from the left or right.

Fabien Roussel

Fabien Roussel, a journalist, became general secretary of the French Communist party in 2018. He favours re-industrialisation, a shorter working week and retirement at 60, but has also discomfited some on the environmentally-minded left — and attracted bons vivants from the Socialists — by arguing cheerfully that a higher minimum wage would allow people to enjoy “good wine, good meat and good cheese” to benefit the economy and improve eating habits.

Anne Hidalgo

Anne Hidalgo, Socialist mayor of Paris since 2014, is best known for her efforts to rid large parts of the French capital of cars, winning her fans internationally but enemies in Paris and its suburbs. But her poll numbers are in the low single digits and have recently declined, suggesting her hopes for the presidency are remote.

Sources and Methods

At each moment in time, the FT poll of polls includes the most recent voting intention poll from ten pollsters, as compiled by NSPpolls, Europe Elects and FT journalists. The average of their results is weighted to give more recent polls greater influence.

Credit: Source link