This is the final part in the FT series Brexit: the next phase

Brexit is the hot topic of the moment, debated in the media, in business circles and by economists as they try to unpick why Britain’s economy is struggling compared with its competitors.

But as public support for Brexit declines, business becomes more agitated and the trade and investment impacts of EU exit become clearer, there is one group reluctant to discuss the “B word”: Britain’s political elite.

Rishi Sunak, the Brexiter prime minister, has shut down a discussion started by anonymous senior figures in his government about whether Britain should build closer “Swiss-style” links with the EU over time.

Meanwhile Sir Keir Starmer, the Labour leader who once campaigned for a second EU referendum, delivered a speech to the CBI in November in which he only mentioned Brexit once in passing.

Sir Ed Davey, the leader of the pro-European Liberal Democrats, did not mention “Brexit” at all in his biggest speech of the autumn, making only a reference to the need to remove red tape “strangling trade” with Europe.

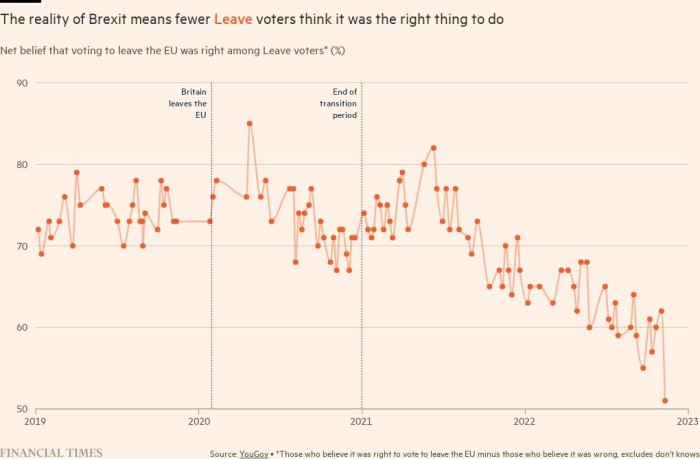

On the face of this it seems as if Britain’s political classes have not caught up with the public. “The truth is Brexit is now probably less popular than it has been since June 2016,” the pollster Sir John Curtice said in November.

YouGov reported in November that 56 per cent of voters thought it was a bad idea to leave the EU and only 32 per cent still thought it was a good one.

But that does not mean the British public has a huge appetite for reopening the divisive Brexit debate, nor do they think there is much prospect of Britain rejoining the EU.

A Redfield & Wilton survey found that only 27 per cent thought it was likely that Britain would apply to rejoin the EU within the next 10 years; only about one-third thought the EU would welcome the UK back.

Starmer and Davey instead talk of making Boris Johnson’s “hard” Brexit trade deal work better without challenging its core tenets: no alignment of rules, no free movement, no European Court of Justice jurisdiction and no big cash transfers to Brussels.

For Starmer, reopening the Brexit debate is seen by his aides as a political disaster waiting to happen, a reminder to Leave voters of how he had once tried to overturn their vote with a second referendum.

Asked after his speech at the CBI conference to explain his thinking on Brexit, the Labour leader said: “We are not going back to the EU. That means not going back into the single market or customs union.”

“He is thinking about Brexit but he doesn’t want to have the whole thing getting out of control, so you’re plunged into a new speculation about whether [the UK] is going to rejoin the single market or customs union,” said one senior adviser.

The issue is particularly problematic in the seats Labour needs to win back from the Tories at the next election. The heaviest concentration of Leave voters coincide with key “red wall” target seats in areas such as north-east England, Lancashire towns and the midlands.

Kevan Jones, Labour MP for North Durham, was a Remainer, but said the issue should be left well alone: “It’s a done deal. We’ve left the EU. We let people have a choice — you can’t keep revisiting it.”

Talking about reversing Brexit is also seen as a doomed electoral strategy by the Lib Dems; the party’s old south-west heartland seats were among the most pro-Brexit constituencies in the country.

As for Sunak, Tory Eurosceptic MPs are an ever-present threat if he deviates from the true path of Brexit. Lord David Frost, the former Brexit minister, has claimed that pro-Europeans are trying to “soften up” the UK for a potential return to the EU, while Nigel Farage, the former UK Independence party leader, is threatening to return to frontline politics if the Tories go “soft” on the subject of Europe.

Both Labour and the Lib Dems, who could find themselves working together in a hung parliament after the next election, talk about improving — not ripping up — the Johnson Brexit deal. Or as Starmer puts it: “Make Brexit work”.

Labour hopes that with improved relations, including resolving the vexed issue of the Northern Ireland protocol, it might be able to renegotiate side deals, such as a veterinary agreement to reduce border checks on foodstuffs, or a deal to make it easier for musicians to tour Europe.

Sunak also believes that if the Northern Ireland row is settled — still a big “if” — he can leverage his initially warm personal relations with French president Emmanuel Macron and European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen and gradually reduce trade friction over time.

Whichever party wins an expected 2024 election, relations with the EU might be expected to warm as the bitterness of Brexit fades and both sides confront common challenges like energy, migration and the strategic threat posed by Russia and China.

But if Britain’s economy continues to lag other EU competitors, will there be a new push sometime in the next parliament for a more fundamental redrawing of the relationship, or even rejoining?

Dominic Grieve, former Tory attorney-general, said that Britain’s entry into the EU in 1973 came as a result of the UK being “a declining country with less global reach and influence” deciding it was better off in the club.

Some politicians say it will take a generation for the issue of whether to rejoin to come back. “I think it will come back faster,” Grieve said. “This debate has never gone away and will continue.”

Sir David Lidington, deputy prime minister in Theresa May’s government and longtime Europe minister, said that if Sunak wins the next election he could use his own mandate to improve relations with the EU.

“If it’s Starmer, I think he would want the reset to go further,” he said, adding that Labour might seek closer institutional relationships. But he warned that anyone who thinks single market access or customs union membership would be an option for Britain without free movement would be “disappointed”.

But David Jones, deputy chair of the pro-Brexit Tory European Research Group, pointed out that reversing Brexit was “not that easy”. “It’s not something that could happen overnight. It would take the best part of a decade,” he said.

“You’d have to have a national conversation, probably another referendum and then you’d have to negotiate with the EU, which would probably want us to join the single currency,” he added

“I’m not sure if either of the two big political parties would have the energy or inclination to go through that process.”

Credit: Source link